Black Wall Street

Tulsa’s Greenwood District in the early 1900s—known as Black Wall Street—offers important lessons for Americans of all colors today. Please share these lessons with others.

Two big things happened in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma in the early 20th century: Starting around 1905-06, an influx of black Americans created a neighborhood-sized microcosm of liberty, productivity, prosperity, and general human flourishing.

The black people of Greenwood created so much wealth that it was dubbed, Black Wall Street.

Then, less than twenty years later, in 1921, angry white supremacists, consumed with jealousy and hatred, murdered the free black people of Greenwood and burned down their homes and businesses.

Black Wall Street, and its bloody destruction, offers important lessons for us today, if only we remember and think.

Building Black Wall Street

Black Wall Street emerged in the early 20th century, fueled by an influx of black Americans seeking better opportunities during the movement scholars sometimes call the Great Migration: growing numbers of black Americans moving from rural parts of Southern states, after the Civil War, to urban areas in the North and West.

The Greenwood District, located on the Northern side of Tulsa—with its bustling businesses, successful professionals, and vibrant cultural scene—became a beacon of hope and a destination for many black Americans at the very moment Democrats were reinforcing the Ku Klux Klan and enforcing Jim Crow laws across the country.

Many of the opportunities in Tulsa and the surrounding area resulted from the oil boom of the early 1900s. There wasn’t much in Tulsa, at that time, and those trying to build new businesses needed help, desperately. Free black Americans took a risk that their willingness to work would be valued by Oklahoma businessmen more than Oklahoma businessmen disliked the skin color of black Americans.

Before the oil boom, in the late 1800s, land runs made it possible for Americans with little capital, including poor black Americans, to buy tracts of land and build and own homes. By the early 1900s, according to the Oklahoma Commission on the Tulsa Race Riot, there were 50 all-black townships in the United States. 20 were in Oklahoma.

The population of Tulsa exploded from 10,000 people in 1910 to over 100,000 just ten years later. Over 12% of Tulsa residents were black. Nearly 100% of the people living in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa were black.

To be clear, there was racial tension at that time, even in Tulsa, even around Greenwood. There were white bigots who prohibited black men and women from entering white-owned restaurants and stores.

That bigotry isn’t all that surprising. What is surprising—what’s truly amazing, what’s beautiful—is how the black people of Greenwood responded to that bigotry.

Creating New Wealth By Producing Value For Others

The people of the Greenwood District did not demand race-based affirmative action programs. They did not insist that they were disabled or disadvantaged because of the legacy of slavery. They didn’t expect anything for free. They demanded no government handouts or subsidies or entitlements or special treatment. They didn’t even ask that their children attend the government-run schools that would eventually become instruments of government employee unions.

Rather, the people of Greenwood governed themselves, lived freely, and created new wealth by being productive and trading with each other.

Read that again. Please.

Even and especially against unimaginable challenges and obstacles, black men and women in Greenwood were starting new businesses, building and buying homes, building schools for their children, and prospering.

They married at high rates, divorced at low rates, raised their children to be self-governing, productive, and self-reliant, and took responsibility for their own health, happiness, and well-being.

J.B. Stradford built the first hotel in Greenwood. Simon Berry created a bus line in Greenwood and started a private airline service to fly oil industry leaders in and out of Tulsa. In 1914, John and Loula Williams built and opened the Dreamland Theater on Greenwood Avenue.

John & Loula Williams, and their son, in 1915.

According to the American Journal of Economics and Sociology:

The 1920 census recorded a multitude of African-American-owned businesses in the community, including billiard halls, clothing stores, music shops, furniture stores, confectionaries, meat markets, hotels, restaurants, and a movie theatre. According to the 1921 city directory, Greenwood comprised 191 businesses. It was also home to a library, two schools, a hospital, and two newspapers.

As black Americans created new wealth in their Greenwood businesses, what did they do? Many expanded their businesses by hiring black Americans looking for work.

When white supremacists in Tulsa refused to serve black people, what did the black people of Greenwood do? They didn’t demand federal or state public accommodation laws. They didn’t try to use government power to command what other Americans did with their own property and their own businesses.

Rather, black people in Greenwood offered to serve black people.

As more black residents of Greenwood prospered, more black residents of Greenwood wanted restaurants, clothing stores, theaters, etc., which provided markets for other entrepreneurial residents of Greenwood to open those kinds of businesses and offer those kinds of products and services.

Free, productive black people in Greenwood were trading, economically, with other free, productive black people in Greenwood.

As growing numbers of black-owned Greenwood businesses made purchases from other black-owned Greenwood businesses, economic growth and overall levels of prosperity in Greenwood skyrocketed. The more successful business owners in Greenwood turned profits into capital by offering startup business loans to fellow Greenwood residents who developed sound business plans, paving the way for black-owned banks in Greenwood.

The Stradford Hotel had 54 rooms and was considered the finest hotel in Tulsa. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

When Booker T. Washington visited Tulsa in 1905, he was profoundly moved by what he saw in the Greenwood District. The independence and freedom and productivity of Greenwood residents inspired Washington’s own effort—along with his friend, Julius Rosenwald, a Jewish businessman who saw the plight of black Americans as similar to the historical struggles experienced by Jews—to build thousands of Rosenwald schools specifically for black children who had been kept out of white schools, which eventually would include Rosenwald schools all across Oklahoma.

Booker T. Washington, Julius Rosenwald, and many residents in Greenwood didn't want black children “integrated” into government-mismanaged white public schools. They wanted something better for black children. And, by all historical accounts, Rosenwald Schools provided academic rigor framed by strict moral discipline for two generations of young black Americans. And it showed.

Blacks in Tulsa were so prosperous that many people nicknamed the neighborhood of Greenwood, Black Wall Street. It’s tempting to say that what happened in Black Wall Street was unimaginable.

Except, it was quite real.

The kind of prosperity that happened in the Greenwood area of Tulsa is exactly what happens when people of any color are free and secure in their property. That’s why the wealth creation in Greenwood came to a screeching halt, in 1921, when that freedom and security were destroyed by angry Democrats, racist progressives, black-haters, Lincoln-haters, Republican-haters, and white supremacists who murdered innocent people and burned Greenwood to the ground.

More Ugly Democratic History

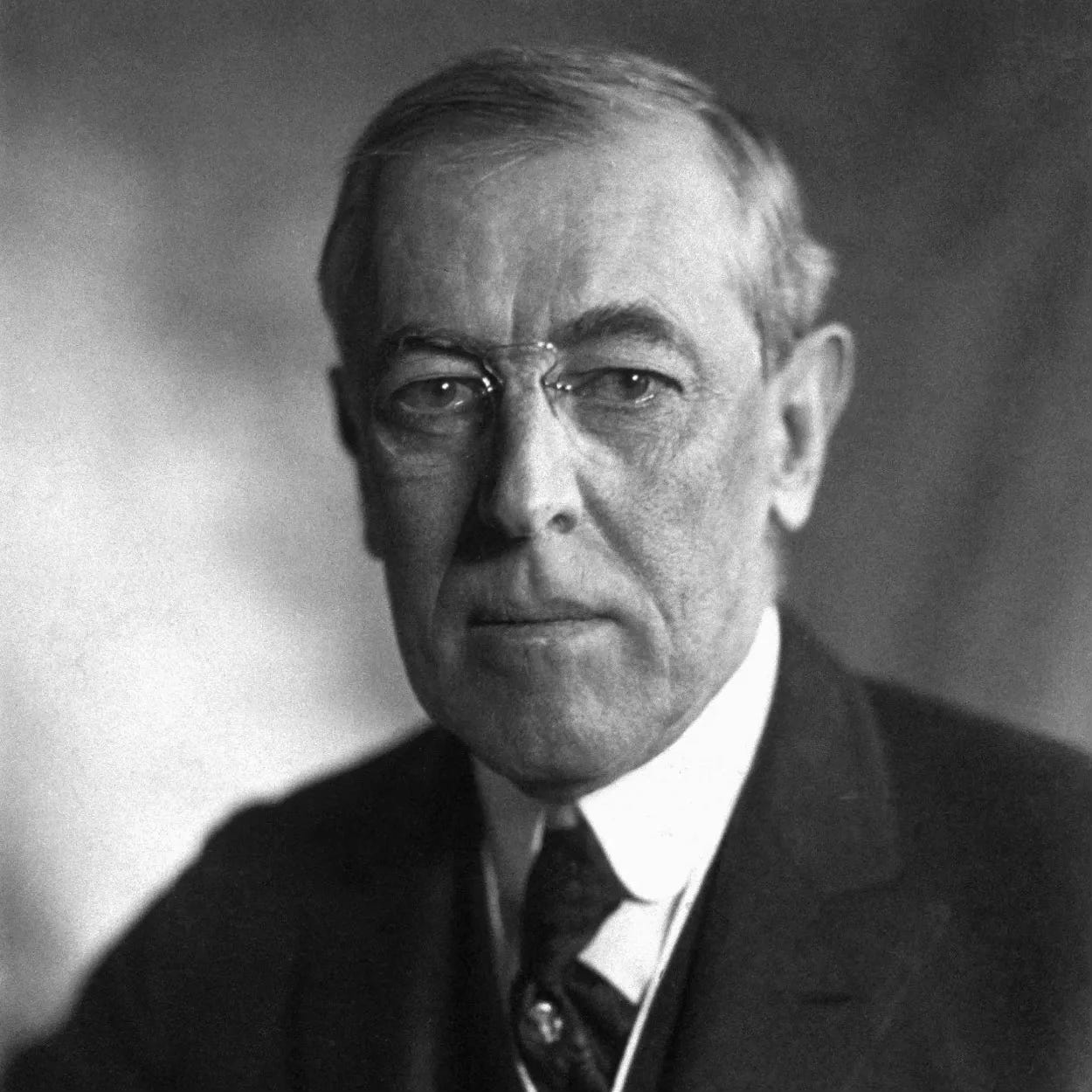

In May of 1921, Oklahoma had a Democratic Governor. America had just been relieved of two back-to-back Administrations of Democrat Woodrow Wilson, a United States President who openly promoted the settled “science” of racial hierarchy and black inferiority, going so far as to segregate by race most of the federal government, including the United States Army and Navy.

Warren Harding, a Republican who spoke openly about equal protection of the laws for the equal individual rights of all citizens—regardless of skin color—had just been sworn in as President only two months before the angry white mobs in Tulsa turned to violence and murder against black Americans.

Perhaps the racists of Tulsa intended to send a message to the new man in the Oval Office who represented the Party of Lincoln?

On May 31, 1921, racial jealousy in and around Greenwood boiled over, culminating in one of the most devastating incidents of racial violence in American history—the Tulsa Race Massacre. The spark was a young black man accused of attempting to assault a young white woman on an elevator. This, after a decade of white Democrats enacting Jim Crow laws, expanding the KKK, restricting where black could go and with whom they could do business, yet watching black residents of Greenwood prosper and thrive.

White supremacists responded in the form of a violent, murderous mob. Over the course of two days, the white mob burned hundreds of homes and looted businesses; they murdered between 150 and 300 black residents of Greenwood and countless more were injured.

The aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre was devastating. The once-thriving community of Black Wall Street lay in ruins, its businesses destroyed, its residents displaced. The economic and psychological impact of the massacre reverberated for generations. Among some, such as he who is writing for you now, it continues to reverberate today.

Lessons

Here’s an important lesson to learn, often ignored, even among those who know about the Black Wall Street massacre:

Black Americans in the Greenwood area of Tulsa, merely one generation after the end of legalized slavery, against strong opposition from Democrats across the country—and in the face of domestic terrorism by the Klan and other Democratic groups—were flourishing.

They. Were. Flourishing.

Fast-forward from the 1920s to the 1960s: Progressives began to argue that because of the legacy of slavery, black Americans cannot flourish without subsidies, affirmative action, and other race-based tribal policies and government coddling. Many progressives today, in 2024, deny that something like Black Wall Street is possible without assistance and oversight from…progressives, especially progressives in government.

Progressives today act as if Black Wall Street never happened. Perhaps they don’t that Black Wall Street happened? Many seem uninterested in history, after all—they find it boring.

Whatever the case, I’m sure many progressive Democrats don’t enjoy talking about Black Wall Street and the race riots that destroyed it because talking about the ugliest chapters of American history requires talking about Democratic history.

Likely, too, they know that acknowledging the ability of free black men and women to create new wealth on their own simply by being free, productive, and secure in their property rights, undermines the premise for the policies and programs aimed at black Americans that many progressives today support.

One thing is for sure: You, the readers of Zetetic Questions, now know about Black Wall Street. You now know what references to the Greenwood District mean. You know what beautiful things can happen when people are free and safe. You know the cruel injustices that result from violating the equal rights of fellow citizens. And you can join me in asking the zetetic questions: Why don’t more Americans know about Black Wall Street? Why don’t more Americans talk about Black Wall Street? Why don’t politicians today learn the lessons of the Greenwood District of Tulsa?