Harry Neumann Matters

The core lesson taught by Professor Neumann is simple and understood by few today: The nothingness of nihilism supports no moral or political cause.

It has been eleven years since Professor Harry Neumann died in May, 2013. A German-born Jew, he and his family left Germany in the 1930s, while Harry was still a young boy, at the very moment progressives were transforming the German state (der staat) into the most murderous experiment in scientific central planning and eugenics the world had ever seen.

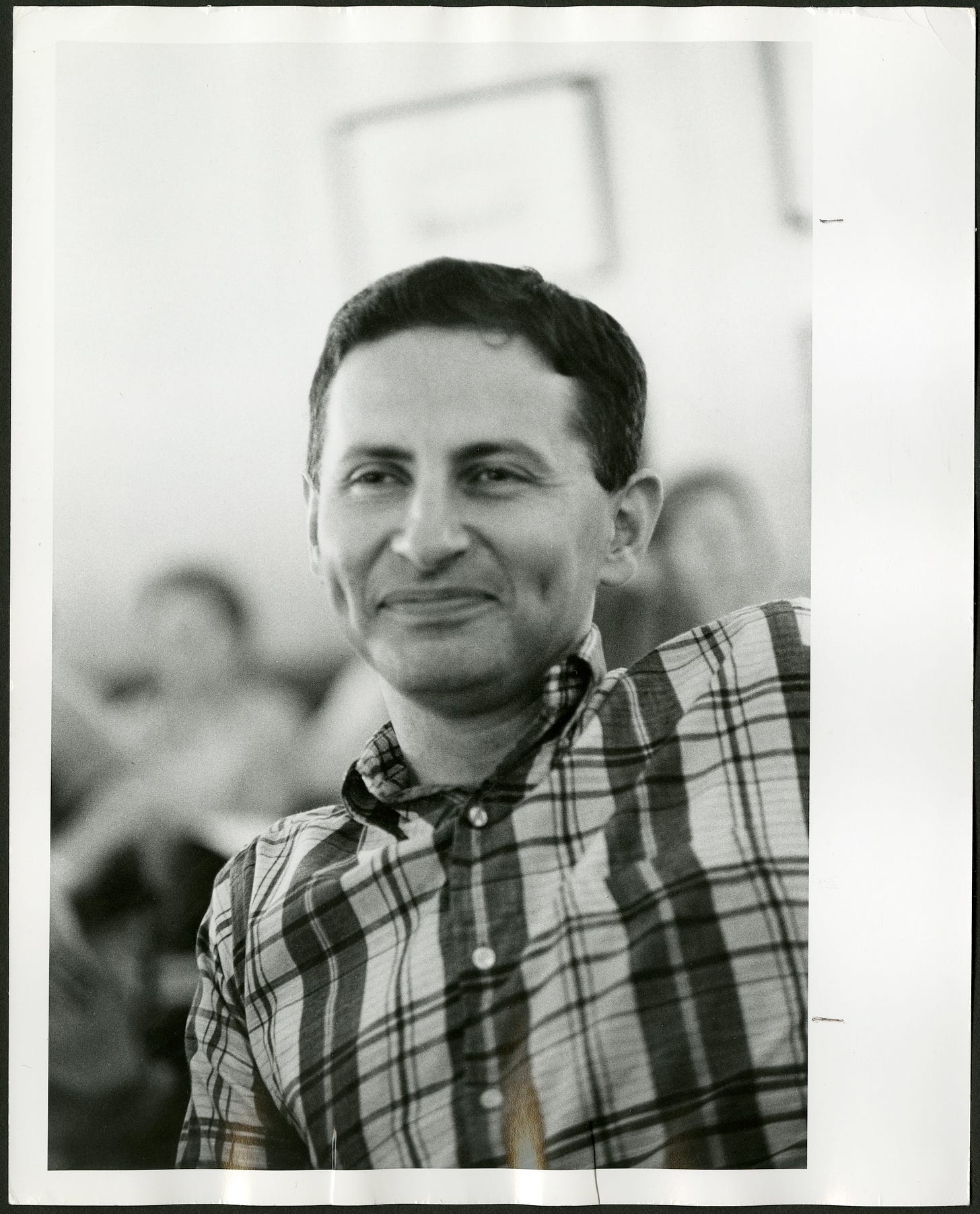

After immigrating to the United States, Neumann was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in the 1940s before serving in the United States Army. He studied at St. John’s College, the University of Chicago, and the University of Heidelberg, before writing his dissertation and earning a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University in 1962.

He was a long-time professor of philosophy at Scripps College and the Claremont Graduate School (as it was then called, before being changed to the Claremont Graduate University), in California, where I spent a decade taking graduate classes, working on my Master’s degree and Ph.D., and writing drafts of three dissertations along the way (which should surprise no one who follows my lengthy social media posts), only one of which I submitted for my doctoral degree. Professor Neumann was one of four members on my dissertation committee.

Professor Neumann was my teacher, in the most important sense of that once reverent title. Few people have influenced my own thinking more than Harry Neumann. No one has taught me more about the fundamental human questions, and the alternative answers to them.

When I was about to graduate from college, I had no idea what to do. I went to my friend and advisor, Paul Basinski. I told him I wanted to keep learning and I wanted to be around thoughtful, serious people interested in studying and discussing important books. I did not know much, then, but enough to know those types are rare, even among academics—or as Professor Neumann would insist, especially among academics.

Basinski told me about Claremont, California, and the two Harrys I would find there: Harry Jaffa and Harry Neumann.

Basinski described Jaffa as the greatest living defender of classical natural right and Neumann as the only intellectually honest nihilist. He suggested that going to Claremont and studying with the two Harrys would be the closest thing to studying with a living Socrates and a living Nietzsche, at the same time.

He was right.

Much to my surprise, I learned after arriving in Claremont that Jaffa and Neumann not only knew each other, they co-taught a graduate seminar over the course of many years, sometimes calling it “Natural Right or Nihilism,” sometimes “Socrates or Nietzsche.”

Great Books

Harry Neumann was the best scholar and teacher of Nietzsche I’ve ever known, and I have spent plenty of time sitting in classrooms listening to lectures on philosophy and reading the books those lecturers write.

Neumann was old-school and excellent in the technical, academic sense of teaching. He’d sit at the front of the room or the end of a conference table with his beaten-up, tattered texts in the original German, usually held together with tape and rubber bands, and the English versions assigned to those of us who are language-challenged, explaining the nuances lost in translations.

He’d do the same with Plato, Aristotle, Machiavelli, Bacon, Descartes, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Kant, Hegel, Marx, Heidegger, and many others. It seemed as if there was not a significant thinker whose great books he had not mastered. Even important books he had not looked at in decades, he could instantly recall in conversation with unmatched attention to minute details.

In the case of Nietzsche, it seemed like Professor Neumann could think like Nietzsche as well if not better than Nietzsche did. If those two were ever to meet, in this world or the next, it would not surprise me if Professor Neumann can teach Nietzsche to Nietzsche better than Nietzsche can teach Nietzsche to Neumann.

Professor Neumann truly was a model of his teacher, Leo Strauss, helping students to understand an author, as best possible, as the author understood himself.

It is impossible to describe the mind of Harry Neumann by reference to some book, or writer, or sect. He was not a Nietzschean. Nor was he an Aristotelian. Nor would any religious group likely claim him as one of theirs—his relentless philosophic inquisitiveness rubs piety the wrong way. And as he oft-remarked: Attributing all morality to a willful, omnipotent God who creates ex-nihilo, who exists beyond good and evil, beyond reason, beyond space and time, doesn’t solve the problem of nihilism; it merely elevates that problem to divine heights.

He was an American. He was a thinking mind trying to discover truth. He was a thinking mind’s mind. He was Professor Neumann.

Impossibility of Nihilism

Professor Neumann presented himself as a nihilist, openly. I am not the only one, however, to suspect that his proclamation of nihilism was a mask, a disguise. His nihilistic façade scared away more timid students, perhaps rightly so.

When asked “How are you today, Professor?” he’d always reply: “50-50.” Not one degree in the direction of doing “well” nor a degree in the direction of doing “poorly”—because “well” and “poorly” both are measured and defined by what is “good.” For the nihilist, there is no good, therefore one cannot be doing “well” or doing “poorly.” Rather, he chose to respond to ordinary greetings with a perfect mathematical representation of moral neutrality: 50-50.

For those who paid attention, however, Professor Neumann showed the human impossibility of an amoral, nihilist world that consists of nothing but power, matter, and moral nothingness. He confronted thinkers, activists, movers and shakers of all stripes, liberals and conservatives of all kinds, and showed that their nihilism does not support their preferred political cause, or any other.

The core lesson taught by Professor Neumann is simple and understood by few today: Nothingness supports no moral or political cause. Every moral and political cause is informed by some idea of what is right. Nothingness, however, is not “right.” Nothingness is nothing.

Strange as it sounds, by confronting students with the moral emptiness of nihilism, Neumann was an unusual and effective teacher of morals.

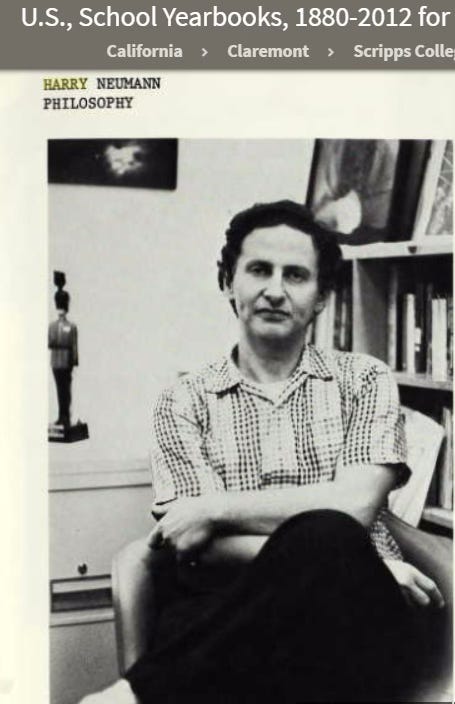

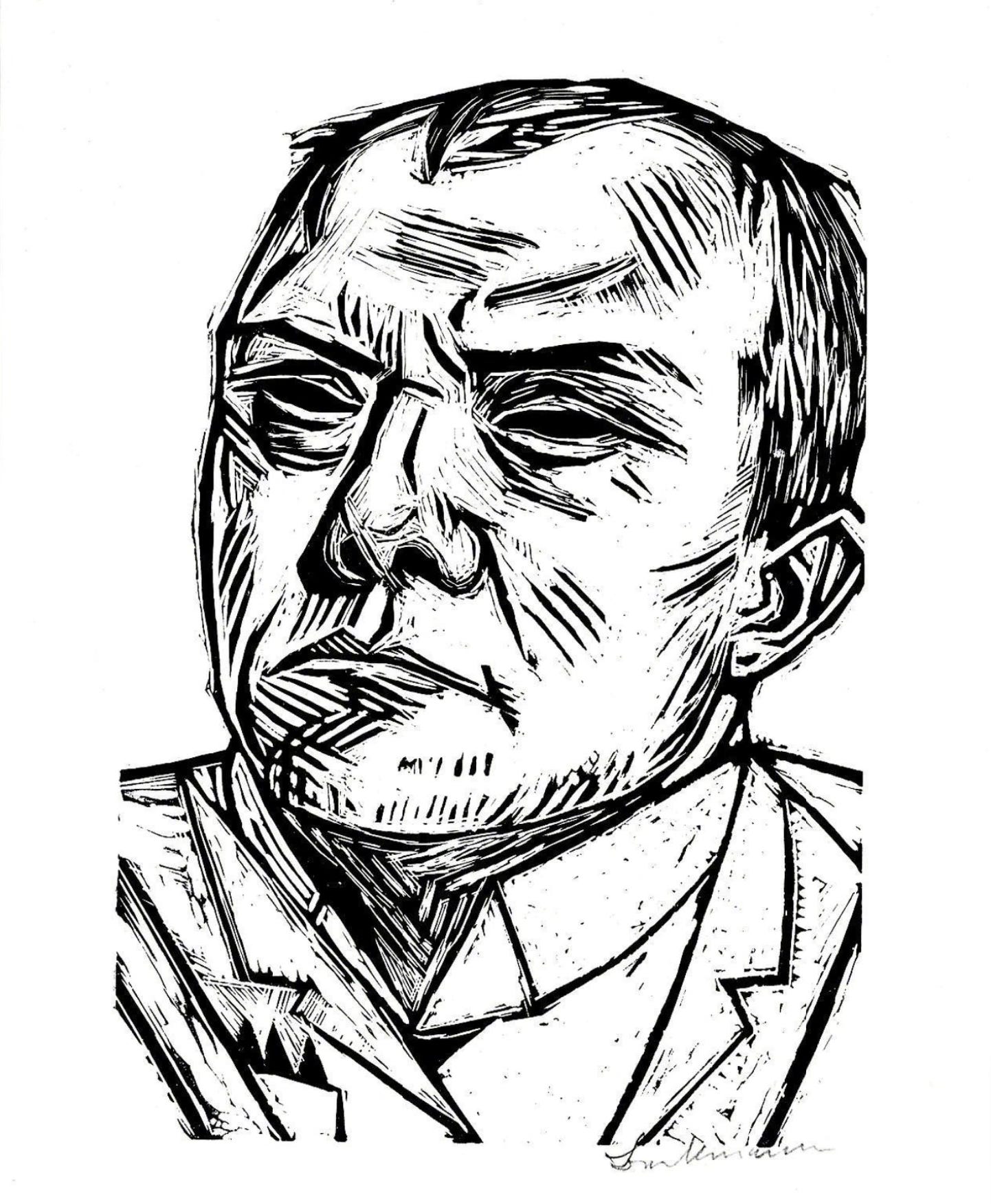

Professor Neumann would often show to his students Max Beckmann’s 1922 self-portrait, which Neumann chose for the cover image of his book, Liberalism. Neumann saw in Beckmann’s expression “firm resolution to face life’s nothingness.” The self-portrait’s “resoluteness,” according to Neumann, “is inseparable from the awareness that it too (the portrait) is as meaningless as everything else in life.”

Student Protests

When the National Guard shot protesting students at Kent State University in 1970, anti-war student protests in Claremont were quickly escalating in violence. Buildings were being set on fire and a package bomb maimed for life a young secretary when she opened it. The Claremont Colleges called an emergency faculty meeting. They were worried that the National Guard would be sent and they did not want the massacre that happened at Kent State to be repeated in Claremont.

In the midst of the hand-wringing and moralizing, newly-hired Professor Neumann stood to remind the faculty that as academics, most of them peddled nihilism in one form or another, explicitly or esoterically, to their students. They were professionals teaching that there is no truth, no right, no purpose, no meaning, only random various cultural perspectives based on moral nothingness.

Wearing his nihilist mask, he congratulated them, and then asked why a group of nihilistic academics cared if students were shot. Did they, after all, think that shooting students was…wrong? Does not a moral wrong imply the existence of some objective moral right? And is not the idea of an objective moral right the very thing those academics denied?

The Claremont faculty dismissed him as a crank, or crazy. That’s because they were too intellectually cowardly to confront the moral challenge he posed. They were more inclined to ignore the contradictions they embraced than to understand themselves, truly.

By challenging them to defend the idea that soldiers shooting students is wrong, Professor Neumann had cut to the moral core of the matter: If there is no right and no wrong, if there is no moral truth, there should be no cause for concern about anything. All he was asking is that the so-called “intellectuals” with whom he worked be intellectually honest about their nihilism.

More, if there is a right and a wrong, then those academics and intellectuals should stop advocating their nihilism and become intellectually honest enough to investigate what right and wrong truly are, what truth is, what the good is.

THAT was Professor Neumann’s point. THAT is genuine philosophic education. Professor Neumann peered deeply into nothingness like few others have done. And as he looked at nothing, I think he saw something.

Like any great, rare thinking mind, Professor Neumann had a way about his thoughts and his speech and his writing. It took considerable effort to delve into the depths of his way and make sense of it. But for those who had the courage to hear him out, and the energy to work and think alongside him, the rewards of insight were beyond measure.

He helped serious students see the darkness of nothing, but in turn that helped them to better see and appreciate the light of truth. If it is true that one cannot know dark without knowing light, so too is the opposite. And I remain persuaded that Professor Neumann, ultimately, was a teacher of light. He illuminated what most people find to be dark.

Philosophy v. Politics

The central theme, or problem, to which Professor Neumann turned his attention—for most of his adult, scholarly life—is the primacy of the moral-political for human life. Human beings are political beings, which means they think and judge and evaluate everything in terms of right versus wrong, justice versus injustice, piety versus heresy.

Professor Neumann saw, and helped others see, the eternal conflict between what is theological, moral, and political (and all politics is theological and moral, as he demonstrated daily in his classes) and philosophy or science (he did not distinguish between the two).

The world as it is known through modern, technological science is a world of empty moral indifference. Modern science dissolves the moral foundation necessary for human political life. Yet, human beings continue to be political because they cannot be any other way. They continue to speak in moral terms of right and wrong. Yet, the science they celebrate reveals an amoral, nihilistic world. Our postmodern world rests on a contradiction

Postmodern people, then, tend to be confused. In one breath, they espouse nihilism and relativism. They mock the suggestion that there is an objective right or wrong. They insist all “values” are relative to culture, or ethnicity, or personal prejudices. Then, in the next breath, they express moral outrage about subjects they politicize, and oppose.

The same people who post yard signs announcing hate has no place in their home and that they love everyone from all backgrounds, will erupt with hateful comments and vile-filled contempt the moment someone mentions the name “Donald Trump.”

Those who exclaim that nothing matters because nothing is intrinsically right or good also insist that “black lives matter.”

Postmodern Americans who insist it is wrong to “discriminate” against certain politically-preferred groups will also ask, rhetorically, “Who is to say what’s right or wrong?” the moment someone suggests maybe the natural family, when possible, is right and good.

Harry Neumann has understood these contradictions better than perhaps anyone in the postmodern, post-truth era.

If all politics is grounded in some confident knowledge about moral right and moral truth—and all political advocates are confident of the truthfulness and rightness of their cause, be they Republicans or Democrats, liberals or conservatives, Communists or Nazis, feminists or environmentalists or multiculturalists or Islamists or Jews or Christians or whatever—then the questioning ways of philosophy/science is always problematic for politics.

Philosophy or science (again, Neumann did not distinguish between them) cannot avoid a quarrel with politics. Philosophy/science is a quarrel with politics because philosophy and science questions the very things politics holds to be unquestionable. All philosophy, ultimately, is political philosophy because all philosophy needs to justify itself, politically. That is why so little that is taught in ordinary academic departments of “philosophy” is worthy of its name: Very few university professors of philosophy worry about being charged with crimes against the state for teaching “philosophy” because, Neumann would argue, they’re not actually philosophizing—they’re not actually questioning or undermining the popular, politically-correct progressive prejudices of our day. Rather, most professors promote those political prejudices.

No scene in the history of human drama better illustrates the conflict between politics and philosophy than the trial and execution of Socrates. What was the main charge against Socrates? Not merely breaking the law, but, more importantly, impiety, something pious Athenians could not and would not tolerate.

Piety was not merely mandated by the ancient law, it was the ground upon which the authority and legitimacy of the law rested. The foundational laws of every ancient city were holy laws, at least in the eyes of pious citizens. They came from the gods. The philosophizing of Socrates was seen by pious Athenians as nothing less than an attempt to undermine the sacred sources of Athenian law and political authority.

That is why Professor Neumann spent the better part of his career trying to understand that strange Greek, perhaps the only truly philosophic soul ever to live, Socrates.

Professor Neumann helped students of politics understand the true, real, primordial, moral ground of politics, always and everywhere. He helped students of philosophy understand the genuinely radical nature of philosophy. And he helped some understand the intrinsic, always problematic relationship between the two. For that, I thank him.

Professor Neumann is gone. He has been gone for more than a decade, and the world is smaller without him. I miss him. But his memory and legacy shall not die. His name and his way of helping others learn to think will survive so long as his students, and the students of his students, remember what they learned from him and share with others. That is one of the reasons I do what I do.