Reality As The Ultimate Oppressor

We used to focus on racial, sexual, and class oppression. Now, nature itself—reality—has become the worst oppressor. If you identify differently than your nature, you are among the oppressed.

This Substack essay began as an attempt to identify and explain a deep contradiction that confuses the postmodern American mind today: The opinion that nature is a standard—or perhaps the standard—by which to measure and judge human actions versus the opinion that nature is something to be conquered, controlled, bent, manipulated, and made to serve the human will.

I will have more to say about that contradiction below.

I found, however, that this subject requires some clarification regarding key words that appear frequently in my writing: classical, modern, and postmodern. Defining those terms provides a perfect segway into the subject of this essay: The contradictory ways Americans seem to think—or feel—about nature.

So let us, then, first discuss these terms, which will illuminate the final subject of this essay before we even reach it.

Chronology

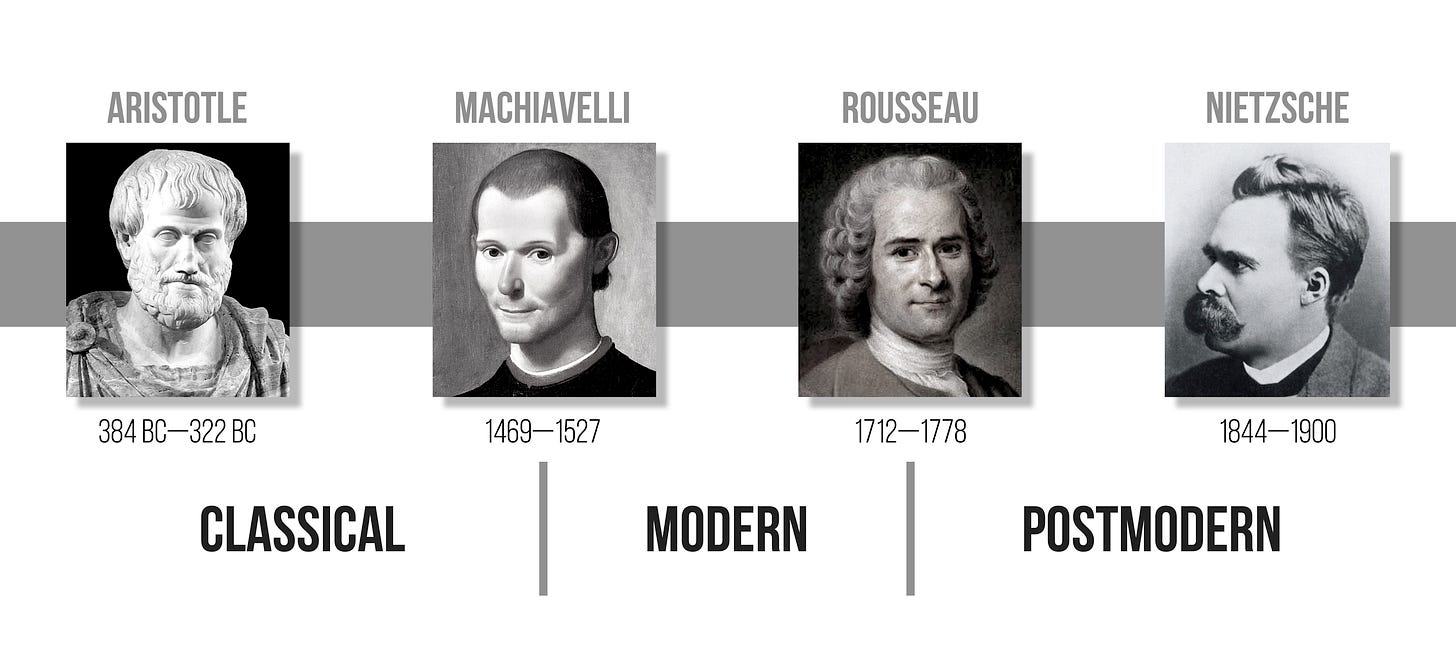

The words classical, modern, and postmodern are adjectives that describe both historical epochs and ways of thinking.

Today, for example, our age is often referred to by thinkers, critics, and scholars as the postmodern age. Yet, I consider myself a classical thinker in many respects, and there are others who agree with many classical ideas and lessons. We few study and agree with classical thought—or parts of it—even as we navigate our postmodern world in 2024.

We are classicists living in a postmodern time.

To understand these terms as historical timeframes, it is useful to first identify the modern period. The other two periods I will define primarily in reference to and contrast with modernity: the classical period is the premodern period, the historical epoch preceding modernity, while the postmodern world comes after the modern period, as the term suggests.

When I refer to the modern world historically, I mean the new modes and orders introduced by Niccolò Machiavelli, the Florence-born Italian polymath, diplomat, and thinker best known for his short book, The Prince.

Machiavelli was born in 1469 and died in 1527, a timeframe that signifies the beginning of the modern period and modern thought. In many ways, modern thought is Machiavellian, a point recently articulated by Harvey Mansfield.

The modern period extends from Machiavelli’s time at least until the controversial works of the French theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was born in Geneva in 1712 and died in 1778.

Rousseau is the fountainhead from which postmodern thought flows due to his profound criticism of modernity, particularly Enlightenment thinkers such as Francis Bacon, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Montesquieu, and Adam Smith.

Rousseau made a significant impact with his two essays, “Discourse on the Sciences and Arts” and “Discourse on the Origin and the Foundations of Inequality Among Men,” often referred to as Rousseau’s First and Second Discourses. These works launched what would later become known as postmodern thought.

Many influential postmodern thinkers who followed, including Immanuel Kant, Georg Hegel, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Nietzsche, studied Rousseau's works and cited him in their writings.

In historical terms, the premodern or classical period within Western civilization refers to the pre-Machiavellian era, the time prior to the 16th century. The classical period includes the contributions of classical Greek philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, as well as notable Roman thinkers, historians, and statesmen such as Cicero, Lucretius, Livy, Virgil, and Marcus Aurelius.

The modern period spans from Machiavelli in the late 15th and early 16th centuries to Rousseau in the mid-18th century, around the time of the American founding.

The postmodern period comes after Rousseau, gaining momentum as an intellectual movement in the 19th and 20th centuries. In many respects, we are currently living in a postmodern world—both in terms of historical timeline and the dominant ideas and assumptions that shape our culture, particularly through our universities in the United States.

Classic Thought

I will begin this section with an apology to those who study the history of philosophy: what follows is merely a thumbnail sketch of how classical, modern, and postmodern thought differ from one another.

Due to space constraints, I cannot delve into each concept in great detail. Therefore, I will paint with broad strokes and, regrettably, skip over many important nuances of classical thought, as well as the modern and postmodern critiques that followed.

For those unfamiliar with the history of ideas, perhaps the most significant concept in premodern classical Greek philosophy is natural right, sometimes referred to as classical natural right. This idea provided the intellectual foundation for the medieval doctrine of natural law, which, while related, is not the same as natural right.

Classical natural right posits that there are objective moral standards inherent in nature—we should never forget that human nature is part of nature—that can be discerned and understood through unassisted reason. These moral standards are universal and apply to all human beings, transcending social conventions, customs, and manmade laws.

Moreover, natural right offers a natural, universal moral standard by which social conventions and laws can be judged as more or less just, moral, and wise.

Aristotle, who perhaps best represents classical thought, recognized that different regimes possess different laws, reflecting varying opinions about what is just and unjust, honorable and shameful, right and wrong. He argued that it is possible to objectively assess which regimes are (more) correct and just versus those that are (more) incorrect and unjust by using human nature as the objective, universal standard for evaluating particular regimes and cultures.

Classical natural right distinguishes between nature in the sense of natural instincts, desires, and appetites that all animals have, versus the natural capacity for moral (or immoral) choices that only human beings have. Humans are the only beings capable of making deliberate choices that sometimes go against their instincts, desires, and appetites. We know, for example, that sometimes it is good to swallow bitter medicine, or refrain from indulging in something we badly crave or covet.

For beings that have a capacity for moral choice, what is right and what is pleasurable are not always the same thing.

Some irrational animals have an instinct or an appetite to devour their own young, and they do. This behavior is “natural” in the sense that these animals have no choice but to follow their instincts; they are, quite literally, slaves to their appetites.

A human being, too, might experience a desire to devour his own child. If he did, classical thinkers would disapprove. They would not justify filicide or familial cannibalism by saying it is “natural.” Rather, classical thinkers would point out that human parents—unlike the irrational beasts of the jungle—have the capacity to make moral choices and can and should choose to refrain from harming or devouring their own child, even when they may feel a desire to do so.

Classical natural right is emphatically not about succumbing to every appetite or instinct. It is about choosing to do what is right by nature, beginning with the recognition of fellow human beings who share the same human nature and treating them as beings of worth, rather than as objects to be exploited or discarded.

Just because orangutans do it doesn’t mean it’s right, by nature, for humans to do the same.

The understanding that reason is inherent to our nature—that it connects the human mind to the reality into which we are born—is inseparable from classical natural right. Nature contains within itself rational standards of moral right, and through exercising reason and studying human nature, the human mind can discover what is universally and objectively morally right.

This philosophical understanding of natural right sometimes fueled utopian speculation, such as that found in Plato’s Republic, regarding the nature of a perfectly just regime. It sparked a philosophical restlessness and a growing awareness that one's own regime and a good or morally decent regime might differ significantly. Classical philosophy can be political dynamite.

Classical natural right also led to philosophical concepts like Plato’s mysterious Idea of the Good, the ultimate being beyond being—an idea that is both abstract and inscrutable, not unlike the singular God that cannot be compared to anything else described in the first book of the Torah.