Science Then and Now

When it aligns with a certain political agenda, we are instructed to “follow the science.” But what is science? How does modern science differ from the classical version? Which is better?

With few exceptions, the modern world is wildly enthusiastic about science. When there is doubt about what to do—such as after the outbreak of a terrible novel virus created by science—many insist we ought to “follow the science.”

(We should ignore, apparently, the glaring fact that “following the science” is precisely how the terrible novel virus came to be in the first place.)

Whether we should “follow the science” is, in part, a moral question. Is it right, just, or wise to follow the science? That seems odd, upon reflection, because when most of us think about science, we think of a realm of facts and data and technology, not right and wrong, or justice and injustice.

Science doesn’t address moral questions. Science provides no moral answers.

That view of science, in the sentences immediately above, reveals much about the victory of modern science over the classical understanding of the subject. Yet, modern science is not superior to classical science, without any qualifications. Modern science is not simply, unqualifiedly good. Classical science was not simply, unqualifiedly bad.

To trot out a few examples: Modern science created the miracle of information that you likely have in your pocket right now—or are looking at as you read these words—the smart phone. That’s handy. Modern science also introduced to the world nuclear power plants and nuclear warheads, both undreamt by classical thinkers.

On one hand, modern science can cure many diseases; modern science causes many diseases; and, modern science (or at least branches of it) cannot define what a woman is.

On the other hand, classical science could not cure many diseases; it did not cause many diseases; and, it understood quite well what a man is, what a woman is, how they complement each other, and both the natural and socially-constructed differences between them.

So which is the better science: Classical or modern?

Like many subjects in life, choosing one over the other involves trade-offs. It’s not a simple matter of either/or.

Modern science offers certain advantages, for sure. And, if we ignore or forget the classical view altogether, we lose entire and important realms of human understanding, including the notion that there are objective moral facts—objective moral truths, discoverable and knowable via scientific inquiry—an idea that seems impossible to many college-educated (post)modern Americans today.

Defining Our Terms

As is typical in a Zetetic Questions essay, let us here clarify, define, and remove ambiguity from some key terms. When I speak of classical science, I am referring to classical Greek and Roman thinkers such as Socrates, his student Plato, and Plato’s student Aristotle, as well as Cicero, Seneca, Lucretius, and others.

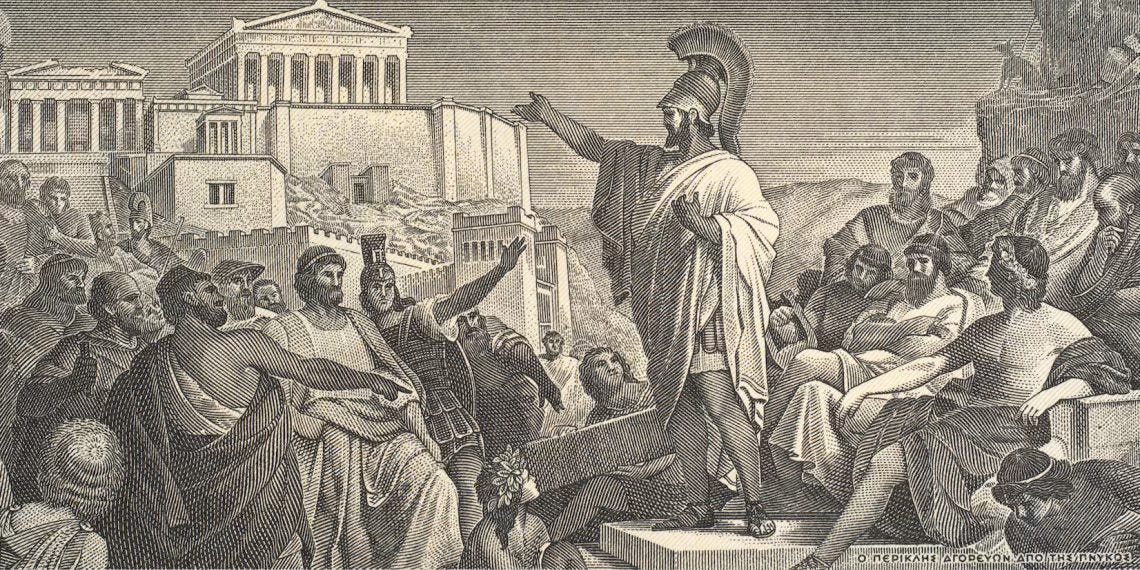

Classical antiquity, at least in the Western World, stretches from the Athens of Pericles, the Peloponnesian War, and the beginning of the Roman Republic, in the 5th century BC, through the rise of the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD, to the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century AD.

That whole period of approximately a thousand years, I consider to be “classical.”

It might also be helpful to keep in mind that our English word science comes from a classical Latin root—scientia—pronounced skee-en-tee-ə—which means simply “to know.” Classical thinkers made no distinction between “science” versus “philosophy,” as there is in our modern world today.

Many people today assume that whatever happens in, say, academic philosophy departments, it is not “science.” Science requires white lab coats, beakers, and Bunsen burners.

Aristotle, for example, would not have recognized this kind of divisions. He would have viewed these subjects as all parts of the same whole—the same reality—about which a thoughtful individual can inquire, observe, reason, study, discuss with others, and learn.

If you asked Aristotle whether investigations of human history and human nature—or matter, motion, and energy—are exercises in science or philosophy, he would’ve answered: Yes.

Portrait of Machiavelli by Santi di Tito.

By modern science, I mean the modern view of the world that originated with thinkers such as René Descartes, Francis Bacon, and above all, Niccolò Machiavelli. These authors and researchers, and others, in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries, ushered in a revolution of thought regarding how human beings understand themselves, the world around them, and the relationship between the two.

While modern science has developed much since then, all of modern science still rests upon the basic modern premises, which we will discuss shortly. First, however, let us summarize classical science so that we can properly distinguish it from modern science.

Classical Science

For classical thinkers, there was a wide range of ways of knowing or coming to know, and whether one called that “science” or “philosophy” or some other exercise of an active, inquiring mind, didn’t really matter.

Aristotle, in particular, demonstrated four causes that, when combined and viewed as a whole, provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the different natures of different kinds of beings.

Those four causes are:

Material cause (the matter a thing is made of).

Efficient cause (how a thing was made or came to be).

Formal cause (the form or shape of a thing, how a being extends into physical space).

Final cause (the ultimate or highest purpose for which a thing exists).

There was something important to the completeness—the comprehensiveness—of the classical view. Let us offer an example:

If one wants to know the nature of a dog, to know what a dog is (as well as what a dog is not) as fully as a human being can know such things, then of course it’s important to know the material causes of a dog.

Of what kind of matter, or material, is a dog made? A dog consists of many organs; those organs in turn are made of certain kinds of tissue; that tissue is made of certain kinds of cells.

All that is important, yes. And, it’s important to know the efficient cause of a dog, or how a dog comes to be. It adds to our knowledge to know that dogs grow from puppies, and puppies are generated by the combined reproductive materials of one male and one female dog.

Beyond all of that, the form or shape of a dog tells us much about the beauty and health of a dog.

When a dog has a form that is long, slender—not bony, but trim, lean—the dog is likely healthy and physically fit. When the shape of a dog reminds us of an overstuffed sausage—when a dog is as wide as he is long—we know the dog is overweight, probably obese, and prone to all kinds of health problems.

All of that knowledge would be incomplete—one would not fully know what a dog is—if one did not understand the final causes served by the dog—the final purpose of a dog—including the companionship, unwavering love, security, and trust that a dog provides to a good person who treats the dog well.

A cellular biologist might know much about the cellular activity within a dog’s liver. Yet that knowledge of a dog remains incomplete without knowing the joy of coming home to a dog who is healthy and truly delighted to see his people, his tail wagging uncontrollably with excitement.

A dog is a cluster of cells, it’s true. And, a dog is more than that, much more. A good dog provides companionship and security. A good dog barks at strangers who seem threatening. If a dog is treated well and, still, violently attacks the people with whom he lives, and ignores threatening strangers, that is a bad dog. Something is wrong with that dog. That dog is defective in some way according to teleology, the study of what a dog ought to be, according to its nature, when fully grown, fully mature.

All that knowledge is included within the classical model of science.

There are many, many other examples. Studying material and efficient causes can reveal much about the nature of the sound waves of which music is made. Yet, again, that knowledge of music remains incomplete without knowing the purpose of a composer who assembles and arranges sounds, rhythms, and harmonies in ways that inspire and uplift us, the experience of feeling one’s own soul swell and rise from a moving musical score.

One of the most interesting of all subjects is the study of human nature. The material and efficient causes of human beings are not typically subjects of great dispute, though recent fads have led many (post)modern people to forget that human nature is intrinsically binary, that every human being comes to be, naturally, by the reproductive materials of one male human being combined with the reproductive material of one female human being.[1]

Classical thinkers wanted to know nature—they wanted to investigate nature, including our own human nature, via science—so that we can know better how to live according to and in alignment with nature. What is the final cause, the ultimate or highest purpose, of a human life? To what great end or goal do all human choices and actions point?

Understanding what is right by nature—summed up in the idea of natural right—and living harmoniously with nature—understanding nature not as something to be conquered and controlled, but as a non-arbitrary, objective guide for how we human beings ought to live—was necessary in order to be good, and to live a good life.

According to classical science, the main way we add to our knowledge about nature—the main methodology of “science”—is a combination of our sense perceptions—seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching—and reasoning about what those perceptions mean. Classical thought held with great confidence that the world we experience through our senses is closely connected to the world as it truly is.

All of that would be radically questioned by modern science.

Modern Science

The modern view, which we can rightfully refer to as technological science, is focused much more on making and doing things, which places great importance on material and efficient causes, while often ignoring and sometimes openly rejecting formal and especially final causes.

In short, modern science accepts the first and second causes of classical science (material and efficient); modern science rejects the third and fourth causes (formal and final).

Modern technological science, beginning in the late 1500s and early 1600s in the notebooks and scholarly tracts of thinkers we mentioned earlier—Descartes, Bacon, Machiavelli, and other Renaissance figures—breaks with the classical view, radically, in at least three ways:

FIRST, modern science is characterized by deep distrust of human sense perception. The world we perceive through seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching is NOT necessarily the world as it truly is.

We see with our eyes, for example, railroad tracks converging in the far distance. Yet, the tracks never actually converge. It’s an illusion.

A ripe apple appears red in color, yet, the redness is not actually in the apple. When light is shined, the apple absorbs all the colors of the spectrum except for red. Wave lengths of light that appear red to the human eye bounce from the apple and strike the rods and cones within the eye. The result is an apple that appears to be red because it looks red to a human eye, yet the apple is not actually red.

Turn off the lights, and the apple that appeared to be red is red no longer. It becomes black.

Hold a large seashell to your ear, and what do you hear? The ocean. Yet, it’s not really the ocean. The hollow cavity of the shell acts as a natural resonator, amplifying sound waves from the surrounding environment. When you hold the shell close to your ear, the ambient sounds, including air movement and environmental noise, resonate within the cavity of the shell. This resonance enhances certain frequencies of sound, creating an auditory experience that resembles the sound of ocean waves.

But you’re not actually hearing the ocean.

A major premise of modern science is the insight that our eyes, and all of our senses, often deceive us. This is why modern thinkers, such as Immanuel Kant, made a distinction between that which is phenomenal and that which is noumenal:

Phenomena are everything we experience through our senses, what we see, taste, touch, smell, hear, and how we understand those sense perceptions, intellectually.

Noumena, by contrast, are what external beings actually are, or things-in-themselves, not as we experience them through sense perception. In the phenomenal realm—how we perceive objects—the railroad tracks converge, or appear to converge. In the noumenal realm—how things are in and of themselves, without being perceived or observed—the railroad tracks are parallel; they do not converge.

Immanuel Kant (22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804)

Some historians of science label the emergence of modern science as the “epistemological turn,” which is why modern science replaces classical observation, sense perception, and reason, with the modern “scientific method.”

For modern science, we cannot trust our senses. The world we experience through our senses is not the way the world really is. It’s much wiser, therefore, to trust the results of well-designed experiments that account for the distorting effects of human sense perception.

SECOND, modern science rejects the classical view that we should know nature in order to live well, or live according to natural right. Modern science is far more ambitious. It’s purpose is to conquer nature and control it, in the memorable words of Francis Bacon, “for the relief of man’s estate.”

The purpose of modern science, in other words, is to make life easier for human beings and enable people to do whatever it is they want to do.

For modern science, nature is not a guide for how we human beings ought to live. Nature supplies the materials with which we can make and do what we have the will to make and do. The only guide for human beings is human will power. We should do whatever we will to do.

Rather than living according to nature, modern science sees nature as something that should be forced to serve human desires and appetites, whatever they be.

This points to the THIRD striking difference between ancient and modern science: Modern science places great emphasis on technology, or inventing and making tools of various kinds that enable human beings to do what they want to do.

If the goal of classical science was to know—so that we can better choose how to live according to natural right—the goal of modern science is to make our lives easier and empower human beings to actualize their unfettered, unrestrained wills.

The English term “technology” comes from combining two Greek roots — technē, which means the art of making something, and logos, which means reason, logic, knowledge. Technology, then, is reasoning about how to do something, or knowledge of how to create and make something.

What we call technology was, for the Greeks, only one small part of the spectrum of what can be known and understood by the human mind.

Yet, today, technology is more popular than ever, while most of what classical science offered has not survived. Technology thrives because we modern people love inventions, innovations. We love our technology. We love new medicines, new computers, new software. We love the modern promise of conquering and controlling nature, making nature bend and serve the will of human beings, however unnatural the objects of our wills might be.

In the past, there were a few men here and there who fantasized about being women, and, we can say accurately, vice versa, because human nature is binary. Today, however, with advanced surgical, hormonal, and other medical technologies, a man can be made to look like a woman; a woman can be made to resemble closely a man.

Classical scientists would warn us against the dangers of technology unmoored from any moral philosophy, political philosophy, or cosmology. But we ignore their warnings. Most (post)modern people today don’t know about their warnings, and don’t care. We care only about what the next iteration of technology will make possible within the realm of human things.

We are more able than ever to answer questions such as: What next can we make? What will we do next? At the same time, we have never been so ill-equipped as we are now to answer the simple follow-up questions: Should we make it? Should we do it? Is it moral?

Who Was Right?

We, today, are free to ask questions, and serious minds should ask questions: Were the classical thinkers right about science and nature? Were the moderns? Were neither? What should be the purpose of science?

Should we human beings follow nature—should we make choices and live according to natural right—or should we conquer and control nature, do whatever we want with nature, make nature serve our desires and appetites?

For classical thinkers, concepts such as natural moral law, natural justice, and natural right, made sense. They understood that objective, universal moral standards of right and wrong—reliable moral guides for human choices—are woven into the fabric of human nature.

For modern scientists, who reduce all of nature—including human nature—to subatomic particles and tiny packets of energy, natural moral concepts make no sense. Modern thinkers tend to assume that right and wrong are mere human contrivances, nothing more—certainly not natural—and no human moral constructs are more correct or more objective or truer than any others.

All morality is subjective, arbitrary, and unnatural. That is the modern view.

Modern scientists can agree, for example, that to make and detonate an atomic bomb, one must know about the matter of which the bomb is made. The question of what purpose will be served by detonating the bomb, many modern scientists would agree, is not a question that modern science can answer because modern science focuses only on material and efficient causes.

The question of what purpose should be served by detonating the bomb—the question of justice—according to modern science, is merely a matter of personal feelings or subjective values. Justice is not natural, therefore justice cannot be known through scientific investigation.

Yet, Aristotle might reply, the study of the purpose served by detonating a bomb is intrinsically higher and more important than the study of how to make and set off a bomb, because the study of the purpose—the final cause or purpose—informs whether we should build the bomb or not.

These are differences between what classical thinkers called “science” versus what we in the modern world assume “science” is.

Modern science is a study of means, not ends. Modern science has nothing to say about ends, whether they are moral or immoral.

The safe-keeper and the safe-breaker, for example, both study the same technology, and that technology doesn’t tell us which one is right or good and which is not. For every well-designed safe there’s a thief who can break into it. Each studies the technologies of the other.

The engineer who would supply cities with electricity using nuclear energy studies the same science as the madman who would destroy the world with nuclear bombs. The executioner charged with running a death camp and killing large numbers of human beings as efficiently as possible studies the same medical science your physician studies.

With modern technological science, we’ve become experts at means—modern science claims to be able to solve virtually any practical problem—while announcing, proudly, that there is no rightful end, no objective moral goal, no ultimate, highest purpose.

Classical science argued that knowledge of ends is always more important than knowledge of means. Most (post)modern people no longer care.

We live in a modern world best described by Leo Strauss: Retail sanity, wholesale madness. We are sane when it comes to figuring out how to do something. We are crazy when asked if it’s a good thing to do—we assume the human mind cannot answer the question.

Stated differently, educated minds in the modern world have much to say about how to do things, very little to say about why we do them, or whether we ought or ought not to do them.

We know more than ever how to extend human life. We know less than ever how to live well. And it shows. Rates of mental health problems and social pathologies continue to climb, not in the poorest or least developed nations, but in those nations that are wealthiest and most scientifically advanced.

The difference between classical science and modern science can be summed up as the difference between merely living versus living the good life, or a life well-lived. These important alternatives should be front and center in our minds as we are told, with increasing frequency, that we should be quiet, be compliant, not ask questions, and “follow the science.”

[1] A human baby results from one man and one woman, and no other numerical or sexual or gender combinations. One person cannot make a baby. Three or more people cannot make a baby. Two women cannot make a baby. Two men cannot make a baby. These basic truths used to be widely known. They are now rejected by growing numbers of people in the (post)modern Western World who consider themselves to be “educated,” “progressive,” and “scientific.”

Another excellent analysis and commentary. Thank you for continuing your efforts.