The American Founding: Ancient or Modern? (Part 1 of 2)

The answer is: Both. Understanding why the Constitution represents the best of classical and modern thought is a reason for fellow citizens to revisit rather than blindly reject the Constitution.

“Law is reason without passion.”

—Aristotle, The Politics

“Reason…is the voice of God.”

—Rev. Samuel West, Sermon Titled “On the Right to Rebel Against Governors,” Delivered May 29, 1776, in Dedham, Massachusetts

The American Founding was a unique blending of political elements, some ancient, some modern.

First let me define some key terms for the sake of clarity: By ancient, I am referring to the pre-Christian classical world of the Greeks and Romans, featuring thinkers and writers such as Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero.

These classical thinkers, while disagreeing with each other in important respects, agreed that virtue is the ultimate purpose of law, politics, and government. Strange as it sounds to our modern ears today, they argued that wisely-drafted legislation and the counsel of wise statesmen can help citizens become better, more moral people.

This seems odd to most of us today because we don’t have wise, virtuous statesmen. We have corrupt politicians who enrich themselves—and stay in office for decades—by doling out government exemptions, waivers, and taxpayer dollars to politically-connected cronies.

If you find it’s difficult to think about Joe Biden as Commander-in-Chief, try imagining him as Chief Moral Reformer!

To understand better the classical teaching, imagine King Leonidas standing shoulder-to-shoulder with 300 elite Spartan warriors as they fought a million invading Persians at the Battle of Thermopylae, an act of courage in the service of justice that remains one of the most famed stories in history.

Classical thinkers had something like that in mind, not the corrupt, greedy political class that has metastasized in our postmodern America.

By modern, I mean the lowering of political ends initiated by Machiavelli and later Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers who argued that the political goal of a modern regime should be mere protection of rights, not virtue or moral excellence. For modern political philosophy, in large measure, safety replaces virtue; effortless comfort and endless entertainment replaces the demanding requirements for eudaimonia.

Part Modern, Part Classical

When we look at the American Founding, we see parts borrowed from classical thought combined with parts that are quite modern. The United States is both classical and modern, a kind of blended regime, neither wholly one nor wholly the other.

The Americans understood their own revolution, for example, in mostly modern terms. Unlike Aristotle, who taught “revolution” as the unending transformation of regimes from one form to another (monarchy becoming tyranny, and then democracy, etc.), the Americans described revolution as an overturning of the existing unjust political order with the hope of building upon the firm ground of eternal natural right a novus ordo seclorum, a “new order of the ages,” something undreamt by classical thinkers.

There are many other modern elements in the American Founding, among them:

The concept of universal natural rights—inherent in human nature, discoverable by human reason, requiring no special revelation from God to be known, and shared equally by all mankind, a concept unknown in the ancient world.

The rejection of divine right monarchy, Papism, religious persecution, and theocracy in all forms, and the corresponding disestablishment of the church. In America, one’s rights would not depend upon a confession of sectarian faith, as Jefferson stated in Virginia’s Act for Establishing Religious Freedom.

The principle that any government lacking the consent of the governed is morally illegitimate

A written constitution that clearly defines, directs, and limits the powers delegated by We The People to our government, with a view that the only purpose of government is to protect individual natural rights, not save souls, and not provide the economic goods people want.

A written constitution that prohibits all titles of nobility (Art. I, Sec 9) and any kind of religious tests as a qualification for any office or public trust (Art. VI).

The protection of a large realm of individual privacy, where citizens are free to pursue happiness, worship God as they choose or not at all, to employ their labor as they see best and keep what they produce and trade with whom they please, and to speak their minds openly, all without government interference. This wide expanse of privacy was virtually unimaginable in the ancient world, where the premise of government was: Whatever the law does not command the law prohibits.

It is also true that there are important classical features about the American Founding. Among the paradoxes of the early American experiment in self-government is the fact that immediately following a modern revolution, America experienced a founding that was classical in character, complete with law-giving “founders” or “fathers”—something common among ancient regimes, rare in the modern world.

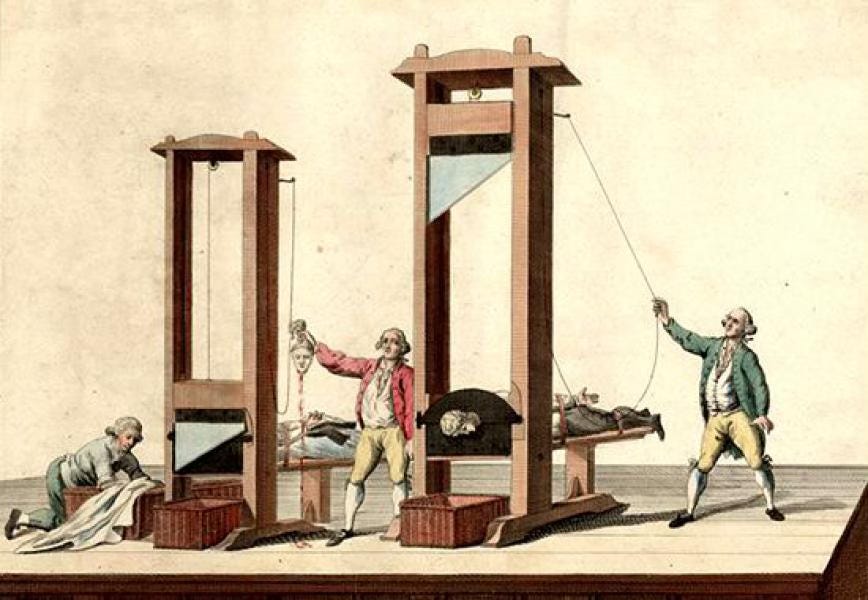

Unlike the scenes of bloody chaos unleashed by the French Revolution, in which the revolution devoured itself and was stopped only by the heavy hand of Napoleon, the Americans quickly moved from overturning unjust laws to adopting new, better laws.

The Federalist Papers were an important cause of the American success, and in particular the teaching of Federalist 49, with its classical, Aristotelian definition of self-government as the rule of reason over passion.

To boot, the pseudonym used by the authors of The Federalist Papers, “Publius,” harkens the authority of classical Roman republicanism.

Classical Political Philosophy In The Federalist Papers

In Plato’s Republic, the lengthy dialogue between Socrates and his several interlocutors is fueled by the question of justice, as they seek to know what justice is and what it would look like in the “most just city” imaginable in speech.

Aristotle, in his Politics, asserts it less as a question and more matter of fact that every political community, by its nature—by human nature—aims at two goods: the safety and happiness of the people. When both are achieved, the result is justice.

Summarizing the theses of Plato and Aristotle, Publius writes in Federalist 51, “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.”

The American Founders understood justice primarily in terms of protecting the equal individual natural rights of each and every citizen. Justice, to the Founders, is achieved through protection of the natural rights of individuals—life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—rights endowed to all humanity by our Creator, and authorized by the “laws of nature and of nature’s God.”

Protection of those rights extends to any act of unjust infringement by others, including private citizens, one’s own government, and foreign powers.

The American Founders reminded us, many times, that those elected to positions of government power are human beings, not angels. Many of our fellow citizens seem to forget that simple lesson.

Yet, self-government always contains within itself a problem: Men are not angels, as Publius famously states in Federalist 51. Human beings are often moved by their passions, their impulses, their appetites, greed, and other feelings, and therefore pure democracy is more likely to produce mob injustice rather than justice.

The authors of the Federalist understood the need for rule of law, a constitution, established to protect the Blessings of Liberty for ourselves and our posterity, among other ends, which is simply another way of describing the God-given natural rights announced in the Declaration of Independence. Thus they sought to establish a constitutional republican form of government containing three separate branches of political power, each largely independent of the others, all designed to protect individual rights and thereby promote justice.

The biggest practical problem surrounding the 1787 Constitution was that it required the ratification of the people, yet it appeared to many Americans to threaten, restrict, and even violate the natural liberty for which they had shed their blood and risked their lives in the Revolutionary war.

The American Revolution and subsequent Founding illuminated for all to see the eternal tension between revolution, on the one hand, and the maintenance of law and order on the other. Yet, without some established order and protection by law, never-ending revolution results in never-ending violence and injustice, further abuses to unprotected individual rights.

If government always poses a threat to individual rights—and it does—so too anarchy poses a similar threat.

Government, then, needs to protect against the passion-fueled, violent injury of rights. And the law, therefore, must be grounded not in passion, but reason. The purpose of The Federalist Papers was to persuade the revolutionary-spirited America of 1776 to become an America under rule of law in 1787. Federalist 49 provided the greatest defense of where the authority of this rule should be derived from: The reason of the people.

Should We Change The Constitution Often?

The question of the reason versus the passions of the public was raised by Publius in the context of a question over what to do with the Constitution should the government the Americans were creating abuses the power the people granted to it.

Any constitution struck off by the mind of men would be less than perfect. But should the people be called upon directly, and perhaps often, if the Constitution appears to be ineffective in separating and limiting the branches of power? It would seem appropriate under a regime “of the people, by the people, for the people.” But Publius ultimately rejects this proposal in favor of a deeper concern for the stability of the law itself.

In Federalist No. 49, Publius considers a possible solution offered by Thomas Jefferson in his Notes on the State of Virginia:

That whenever any two of the three branches of government shall concur in opinion, each by the voices of two thirds of their whole number, that a convention is necessary for altering the Constitution or correcting breaches of it, a convention shall be called for the purpose.

At first, Publius seems to agree with Jefferson.

The people, after all, “are the only legitimate fountain of power, and it is from them that the constitutional charter, under which the several branches of government hold their power, is derived.” That is why Publius’s Constitution provides a process for the people to amend their Constitution when it is required to remedy a constitutional defect or solve a serious problem.

But the amendment process is made rare by being made difficult—requiring (typically) two-thirds of a vote in Congress and three-fourths of the states to ratify an amendment—and for good reason. There is a deeper, inherent problem with frequent appeals to the people to change or transform their fundamental law:

[A]s every appeal to the people would carry an implication of some defect in the government, frequent appeals would in great measure deprive the government of that veneration, which time bestows on everything, and without which perhaps the wisest and freest governments would not possess the requisite stability (Federalist 49).

When the people are called upon, frequently, to fix or repair their Constitution, they are reminded that the fundamental law is defective, broken, and in need of fixing. This detracts from the authority of the Constitution because people will not likely respect, or venerate, much less obey, a law they believe is defective to the point of needing constant repair and improvement.

In short, we shouldn’t amend or change the Constitution in any fundamental way, often, if we want fellow citizens to respect or revere the Constitution.

People tend to venerate what is old and traditional. What is new is by nature suspect—it has not proven itself to be good. Veneration therefore requires the passage of time. But if the American people are frequently refashioning their Constitution, they never have the opportunity to live under an old Constitution because it is always being remade anew.

If, however, the people can adopt the Constitution and then leave it standing largely untouched and unchanged, it eventually becomes old. With the passage of time, the Constitution appears to the American people—if they are wise and respect what has been time-tested and proven to be reliable—ever more worthy of veneration as it becomes part of their own longstanding tradition.

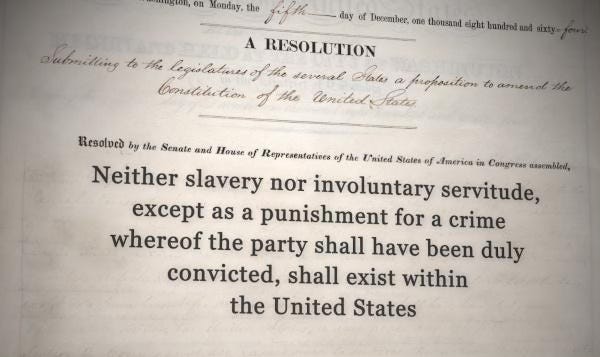

To be clear: This does not mean the American people should never amend the Constitution. They were absolutely right to add the 13th Amendment, for example, and abolish legalized slavery throughout the United States, aligning the Constitution with the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

It means that Americans should not amend or alter the Constitution frequently or for “light and transient causes.”

Do We Still Honor That Which Is Old & Time-Tested?

Stated differently, as time passes, the people become increasingly distant from the creation of the Constitution, thus forgetting to some degree that the Constitution is a product of their own making. This, as we will see, can be a good thing. This is the subtle, almost esoteric teaching careful readers find within The Federalist Papers.

Time bestows veneration because time allows the people to become more attached to the principles and goodness of the Constitution, and reflect less on the act of creating the Constitution.

Time allows constitutional founding (the giving of law) to evolve into constitutionalism (the rule of law).

Time encourages Americans to think of themselves less as law-givers, more as law-obeyers, at least regarding the fundamental law, the Constitution.

What else is required for the American people to value, appreciate, follow, and be willing to defend their own good Constitution? In our postmodern age when millions of fellow Americans assume without investigation that our Constitution is outdated, irrelevant, immoral, racist, and not worth defending, this might be the most pressing political question of our day. It’s certainly a zetetic question for our zeitgeist.

We’ll turn to some of the arguments and solutions offered in The Federalist Papers in our next essay (Part 2 or 2).

Tom, have you done any work comparing constitutions and their approaches to rights. I’m not an expert, but my understanding of the Brazilian constitution is that it promises to deliver all kinds of positive rights. However, despite these promises, it hasn’t delivered.

https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Brazil_2017

Working on this idea of passion without reason. It seems on college campuses these days it is all passion playing out and this I believe leads to civil war. We lose our reason and rely solely on emotion to make arguments. Woodrow Wilson thought it was the Constitution that was the problem, but I think it is a fundamental character trait of people who do not guard their mature reasoning ability and rely solely on their immature emotional reactionism.