The Feelz

Postmodern progressive disciples of Rousseau prefer to talk about how they feel because feelings cannot be evaluated, tested, or refuted. After all, how can one’s own feelings be wrong?

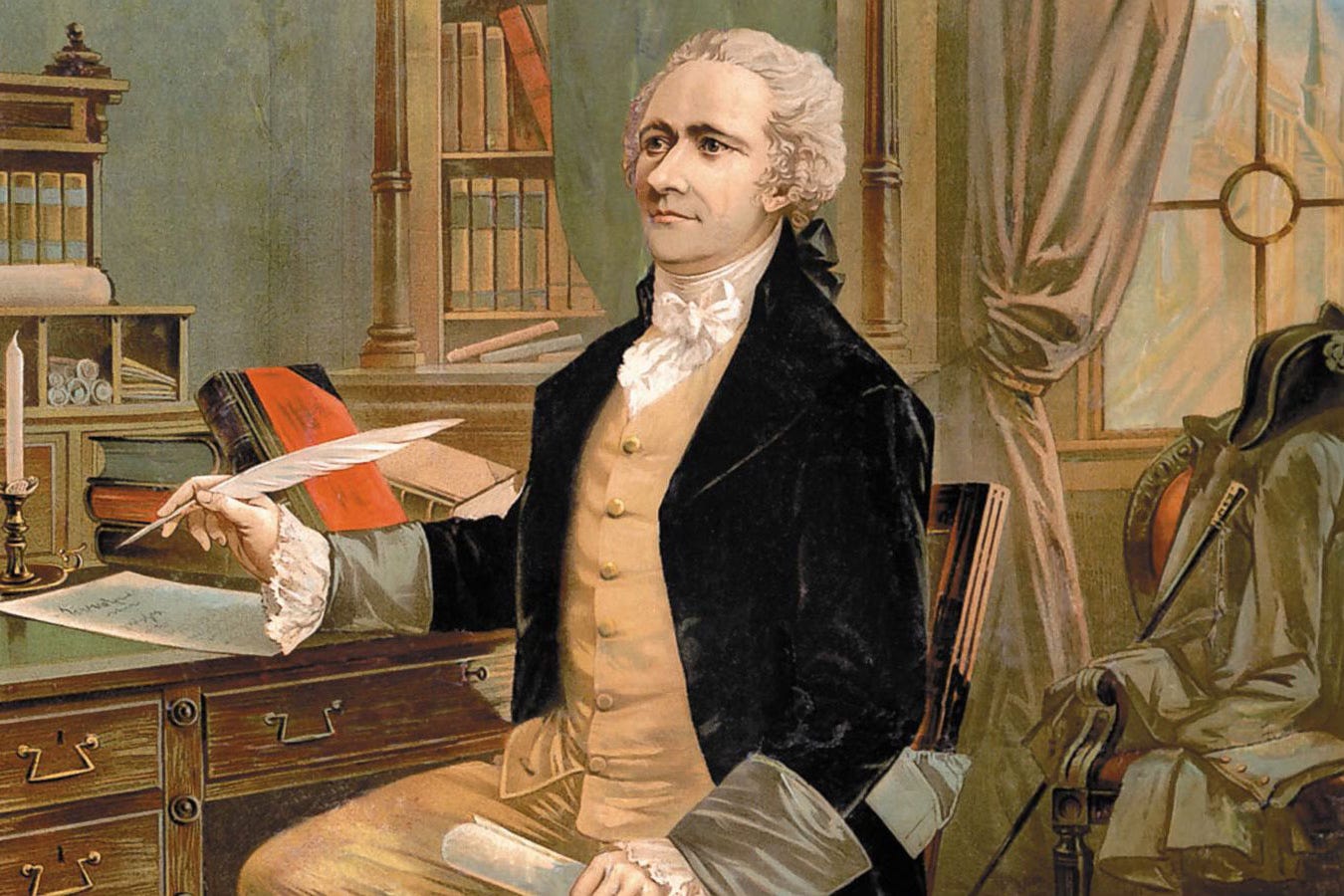

I attended an unusual live performance last night featuring two actors—one portraying Thomas Jefferson and the other Alexander Hamilton—debating each other.

These men not only looked like the historical figures they were representing; they have clearly done their homework. They spoke on topics that were of great concern to both Jefferson and Hamilton, using a vocabulary that reminded the audience of how these learned men of the American Founding spoke and wrote.

It was as close as one could get to witnessing a real debate today between a living Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton.

The event—titled “Hamilton v. Jefferson: A Live Debate”—was hosted by the Aspen Academy in Greenwood Village, Colorado. The entire evening was organized by Constituting America, a group of educators dedicated to teaching a large network of grade school and high school students across the United States about the Constitution.

I have spoken for Constituting America, and they truly are a gem. If your favorite school isn’t taking advantage of the excellent resources they offer, you should change that.

There were no moderators for the debate last night—no partisans pretending to be neutral referees, but really there to promote their own political agendas by helping the dim-witted of the two interlocutors. No, nothing like what we’ve become accustomed to today.

Rather, the two historical politicos addressed questions to and challenged one another, each responding with reasoned arguments and informed opinions: Hamilton asked Jefferson to explain certain Jeffersonian policy positions, and vice versa.

The debate lasted a little over an hour, followed by a brief Q&A from the audience. I don’t recall exactly how long each segment was because I was too captivated by the discourse to glance at my watch or phone.

It was a showcase of serious, learned minds—the towering statesmen upon whose shoulders we used to stand, as a nation. One nuanced yet significant feature that really stood out during the debate, at least for me, was that neither Hamilton nor Jefferson began a sentence with, “I feel like…”

Not once.

This was appropriate and fitting because the real Hamilton and the real Jefferson did not speak or write in the intellectually vacuous way so many postmodern Americans do today.

Thomas Jefferson, for example, at the end of his “Summary View of the Rights of British America,” proclaimed:

Still less let it be proposed that our properties within our own territories shall be taxed or regulated by any power on Earth but our own. The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy but cannot disjoin them.

Jefferson did not say, “I feel like Parliament shouldn’t tax us,” or “I feel like freedom might be a good thing.”

Within the pages of The Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton explained with precision what Aristotle meant by noetic knowledge:

In disquisitions of every kind, there are certain primary truths or first principles upon which all subsequent reasonings must depend. These contain an internal evidence which, antecedent to all reflection or combination, commands the assent of the mind.

In his earlier essay, “The Farmer Refuted,” Hamilton thundered:

The sacred rights of mankind are not to be rummaged for among old parchments or musty records. They are written, as with a sunbeam, in the whole volume of human nature, by the hand of the divinity itself, and can never be erased or obscured by mortal power.

Hamilton did not share his “feelings” regarding certain primary truths or first principles upon which all subsequent reasonings must depend. He did not say, “I feel like people have rights.”

The Feelz

By contrast, listen to your fellow Americans talk today, especially younger people. Many of them struggle not to begin a sentence with, “I feel like…”

To be clear, there are situations when it’s appropriate to share one’s feelings. If your stomach hurts and a physician asks how you are doing, you should tell him you feel like you have a stomach ache.

If you are feeling giddy, sad, scared, excited, or anxious, indeed, share those feelings with the people close to you, who care about you.

Feelings, however, are no substitute for evidence, facts, reason, or the logic of morals and politics. Nothing is more narcissistic and self-centered than saying: “I feel like everyone has a right to free health care,” or “I feel like we need more regulations,” or “I feel like Kamala Harris is highly intelligent and has wonderful policy proposals.”

These kinds of statements turn the discussion to your subjective and fleeting feelings. When you open a sentence with “I feel like…” in place of providing a sound argument, you make your feelings the focus of the conversation.

The conversation becomes all about you and how you feel.

Imagine if you said to someone, “I feel like I am catching a cold.” There would be no serious debate about the pros and cons of the common cold, or the viruses that cause it. The conversation would revolve solely around how you are feeling and what can be done to comfort you and help you feel better.

Using that kind of opening—“I feel like…”—regarding a subject that deserves a thoughtful argument only adds confusion to the discussion.

If you want to make the case for universal free health care, then make the case. Explain who will provide free health care, and why. Don’t talk about your feelings.

If you want to make the case for minimum wage and price cap laws, then make the case. Explain the rightful authority government has to command how much compensation a business owner must offer in exchange for some labor, or how much a business may ask for a product it sells. Don’t talk about your feelings.

If it is morally right for you and fellow voters to take other people’s money in the form of taxes and then waste it on more government boondoggles, then make the case. Explain why other people’s money is really your money. Don’t talk about your feelings.

If Kamala Harris is highly intelligent, then demonstrate it with evidence. If her policies are wise and just, explain how. Don’t talk about your feelings.

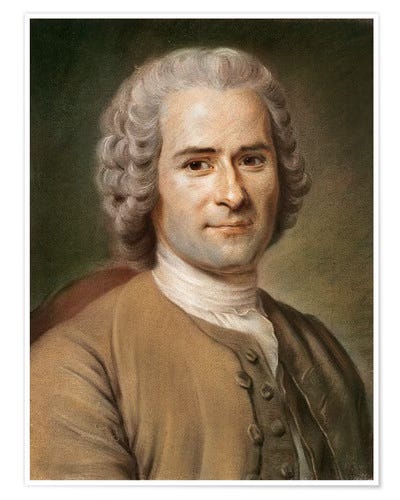

The fact that many Americans today cannot speak about subjects external to themselves without referencing and making the conversation about their own subjective feelings, marks the triumph of the postmodern attack on objective truth, an attack stretching back to Rousseau’s assertion that the human being is an emotive, feeling being by nature, not a rational being.

Postmodern progressive disciples of Rousseau much prefer talking about how they feel—over logical, reasonable arguments—because feelings cannot be evaluated, tested, or refuted. After all, how can one’s own feelings, about anything, be wrong? Feelings are just feelings.

That is why so many young Americans today—even when the topic is not their own health or emotional well-being—even when speaking of external subjects that are outside of themselves—nevertheless begin their sentences with: “I feel like…”

But hearing Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton speak last night, and debate one another, was a wonderful reminder of what human speech—what the Greeks called logos—used to mean, and what it sounded like. It is an artful, beautiful reminder of the uniquely human capacity for reason, reasonable debate, and the rational pursuit of truth.